Be Plus: The striking gallery entrance at Studio Be

Studio Be

with Geoffrey Wilson of Turning Tables NOLA

interview by Paul Oswell

It’s a beautifully sunny January afternoon and I’m meeting friend, bartender and all-round lovely human Geoffrey Wilson to take a turn around the Studio Be gallery in the Marigny. If you’re unaware of this place, it’s a huge, 35,000 sq ft warehouse that acts as gallery and shop window for local artist, Brandan 'BMike' Odums.

You may have seen BMike’s enormous, vibrant murals - they certainly must be some of the most Instagram-ed artworks in the whole of the city. I wanted to catch up with Geoffrey, listen to his thoughts about the art and find out more about the non-profit that he helps run, Turning Tables NOLA.

To quote their own website, “Turning Tables provides both inexperienced and rising Black and Brown hospitality professionals with culturally responsive education, training, mentorship, and the resources necessary to access real opportunity.”

We start our tour. Everything in quotes from here on is Geoffrey.

with Geoffrey Wilson of Turning Tables NOLA

interview by Paul Oswell

It’s a beautifully sunny January afternoon and I’m meeting friend, bartender and all-round lovely human Geoffrey Wilson to take a turn around the Studio Be gallery in the Marigny. If you’re unaware of this place, it’s a huge, 35,000 sq ft warehouse that acts as gallery and shop window for local artist, Brandan 'BMike' Odums.

You may have seen BMike’s enormous, vibrant murals - they certainly must be some of the most Instagram-ed artworks in the whole of the city. I wanted to catch up with Geoffrey, listen to his thoughts about the art and find out more about the non-profit that he helps run, Turning Tables NOLA.

To quote their own website, “Turning Tables provides both inexperienced and rising Black and Brown hospitality professionals with culturally responsive education, training, mentorship, and the resources necessary to access real opportunity.”

We start our tour. Everything in quotes from here on is Geoffrey.

“I became aware of BMike when I returned to New Orleans, around two years ago”, Geoffrey says. “I was told there was a lot more going on in the city since the last time I was here, one of them being this space. We brought the second and third year classes down here. Everyone was just blown away by everything. For BMike to have this spot in the middle of the Marigny-Bywater as it gentrifies is especially powerful. We all had to stop all the time and just think, man, what the hell?!”

You’re immediately surrounded by these large-scale works, full of color and detail. Mixed forms, some political, some expressions of outright joy, all of them inspirational. “What I like about BMike is that he really does the whole range from whimsy to hard-hitting social commentary, and creates in a wider range of media than almost anyone...paintings, installations, sculpture, even inflatables. I’m not spiritual but there’s a mix of energies here, tragedy and hope at the same time. That’s what being Black in America is.”

Many recognizable Black American icons are represented on the walls, some of them new to me as a white European transplant. “This place is a great springboard for further education on black history and pop culture. Everyone that’s represented here? Their lives are worth exploring further.”

We approach a piece in the first hall that depicts the civil rights activist Fred Hampton. “This right here gets me every time. I had to sit down for twenty minutes the first time I saw it. The assassination of the man. It’s so heavy. And it wasn’t too long ago, it’s within many of our lifetimes. It taps into how we deal with modern events, and these things hit hard because you want to participate in protests and be part of these things and then you see what happened to this man and it’s a gut punch. And it still hits me.”

“It’s honestly the most moving piece I’ve seen since the Mona Lisa. There’s power in that for sure, but this is recent history, it’s American history, and it’s something that people need to know about. When I lived in Chicago, I would see cops wearing t-shirts that said ‘We kicked your parents’ asses in ‘68’. I mean, it’s not even subtle.”

You’re immediately surrounded by these large-scale works, full of color and detail. Mixed forms, some political, some expressions of outright joy, all of them inspirational. “What I like about BMike is that he really does the whole range from whimsy to hard-hitting social commentary, and creates in a wider range of media than almost anyone...paintings, installations, sculpture, even inflatables. I’m not spiritual but there’s a mix of energies here, tragedy and hope at the same time. That’s what being Black in America is.”

Many recognizable Black American icons are represented on the walls, some of them new to me as a white European transplant. “This place is a great springboard for further education on black history and pop culture. Everyone that’s represented here? Their lives are worth exploring further.”

We approach a piece in the first hall that depicts the civil rights activist Fred Hampton. “This right here gets me every time. I had to sit down for twenty minutes the first time I saw it. The assassination of the man. It’s so heavy. And it wasn’t too long ago, it’s within many of our lifetimes. It taps into how we deal with modern events, and these things hit hard because you want to participate in protests and be part of these things and then you see what happened to this man and it’s a gut punch. And it still hits me.”

“It’s honestly the most moving piece I’ve seen since the Mona Lisa. There’s power in that for sure, but this is recent history, it’s American history, and it’s something that people need to know about. When I lived in Chicago, I would see cops wearing t-shirts that said ‘We kicked your parents’ asses in ‘68’. I mean, it’s not even subtle.”

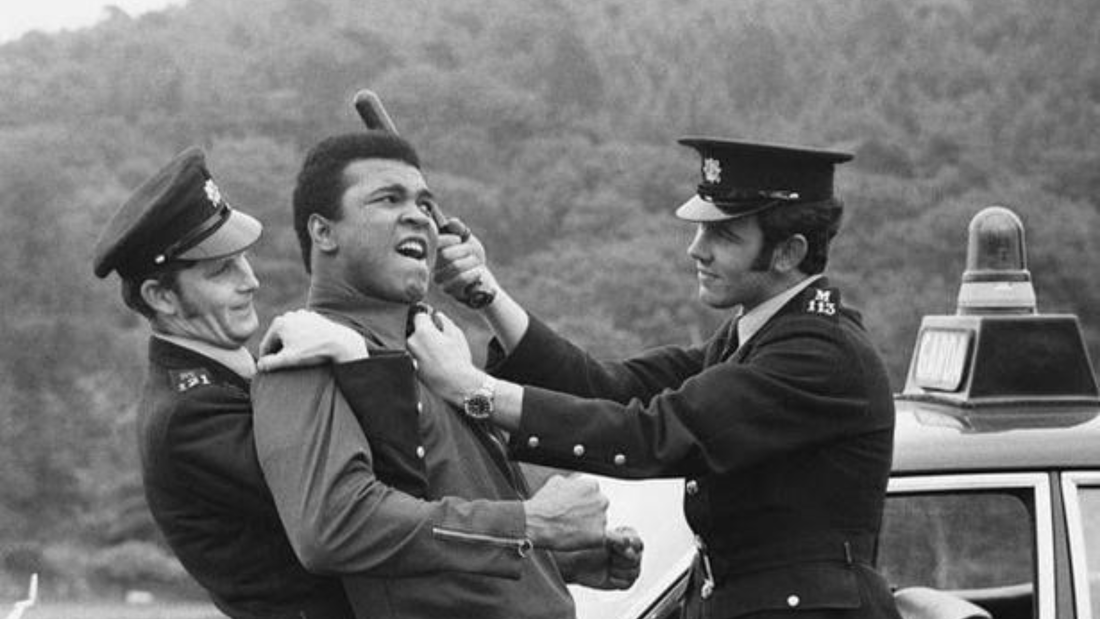

There’s a striking mural of the famous photo of Muhammed Ali wrestling with some cops. “That photo was a playful set-up, when he lost his world titles but he was still popular. But this can still be seen as representing the struggle because even though this specific scene was staged, it is absolutely true of what he had to go through back then. If I had a sports hero growing up, it was him, even though he was flawed just like everybody else.”

One of BMike’s more notable installations is part of a basketball court. Beside it reads a sign: ‘1/3 of Black males will go to prison in their lifetime. 3/10,000 will go to the NBA’.

“This is my second favorite piece. The social statistics here are just mind blowing. I love that BMike, as a high-profile Black artist in this city, can express himself in a space like this. It’s really about time. I’ll come in here and take pictures, but I won’t put them on social media, I’ll just keep them for myself.”

There aren’t many artists using retro arcade game units as a canvas, but Studio Be has four or five of them, each focusing on different ways that Black people move through the world on a daily basis. “I haven’t seen anyone else do this kind of thing, I think these are absolutely brilliant. I think (the police trainer game) is actually a real thing. I grew up with Atari and Nintendo and it’s wild to see arcade games subverted to make artistic statements, and it’s just beautiful.”

“I’m drawn here because most of the art institutions in town represent a history that’s not of interest to me. I find a lot of similarities between here and Chicago. They’re working class cities that are being taken over by people who don’t, by and large, live here. But we get rewarded every year with a party. Mardi Gras is the only holiday that I celebrate, and you can’t have Mardi Gras without Black people, you just can’t.”

I ask Geoffrey about Turning Tables, what it does and how it helps young people wanting to go into the hospitality industry.

“I was living in Portland Oregon, and during their cocktail week I heard about a programme from a friend who doesn’t live here any more named Steve Yamada. I met Touré Folkes (who created the program) in 2019, and It sounded like something I always wanted to do.”

“I’d actually quit bartending at that time, but he inspired me to return and I wanted to get involved. He told me he wanted me to move back down here to help with the second intake, and I started interviewing applicants over Zoom even before I moved down. I set up a job with Jeff and Annene (owners of tiki bar Latitude 29) and that was that.”

“In the booze world in 2007/2008, a lot of bartenders kept their skills close to the vest. Some people would share, and they’re my close friends. I’ve tried to help and disseminate information wherever I’ve been - Pittsburgh, Phoenix, here - just trying to help people. I’ve been the first Black bartender to work at a bunch of local places.”

The program is a dynamic one that involves much more than knowing how to mix a sazerac. “We hopefully will have two intakes a year, and the course is twelve weeks per intake. As well as bar skills, we focus on things like mental health, and how people can advocate for themselves.”

“We have this thing called the ‘externship’, where we place people. We have a guy we just placed for six weeks over at Cure, and if it leads to a job that’s great, and if not it’s valuable experience. Another person worked at Jewel of the South with Chris Hannah and now they have a job there. We have a good hit rate, graduates are managing, running wine programmes, the whole thing. Some people also use their new skills to expand their own businesses.”

It’s an inspiring project, and it seems fitting to hear about it in such an inspirational place. If Studio Be reflects what it is to be Black in America, Turning Tables improves people's chances of becoming what they dream of being.

To find out more about Turning Tables NOLA, go to www.turningtablesnola.org

Studio Be is at 2941 Royal Street, and is open Wednesday through Sunday from 2pm-8pm.

More information here: studiobenola.com

One of BMike’s more notable installations is part of a basketball court. Beside it reads a sign: ‘1/3 of Black males will go to prison in their lifetime. 3/10,000 will go to the NBA’.

“This is my second favorite piece. The social statistics here are just mind blowing. I love that BMike, as a high-profile Black artist in this city, can express himself in a space like this. It’s really about time. I’ll come in here and take pictures, but I won’t put them on social media, I’ll just keep them for myself.”

There aren’t many artists using retro arcade game units as a canvas, but Studio Be has four or five of them, each focusing on different ways that Black people move through the world on a daily basis. “I haven’t seen anyone else do this kind of thing, I think these are absolutely brilliant. I think (the police trainer game) is actually a real thing. I grew up with Atari and Nintendo and it’s wild to see arcade games subverted to make artistic statements, and it’s just beautiful.”

“I’m drawn here because most of the art institutions in town represent a history that’s not of interest to me. I find a lot of similarities between here and Chicago. They’re working class cities that are being taken over by people who don’t, by and large, live here. But we get rewarded every year with a party. Mardi Gras is the only holiday that I celebrate, and you can’t have Mardi Gras without Black people, you just can’t.”

I ask Geoffrey about Turning Tables, what it does and how it helps young people wanting to go into the hospitality industry.

“I was living in Portland Oregon, and during their cocktail week I heard about a programme from a friend who doesn’t live here any more named Steve Yamada. I met Touré Folkes (who created the program) in 2019, and It sounded like something I always wanted to do.”

“I’d actually quit bartending at that time, but he inspired me to return and I wanted to get involved. He told me he wanted me to move back down here to help with the second intake, and I started interviewing applicants over Zoom even before I moved down. I set up a job with Jeff and Annene (owners of tiki bar Latitude 29) and that was that.”

“In the booze world in 2007/2008, a lot of bartenders kept their skills close to the vest. Some people would share, and they’re my close friends. I’ve tried to help and disseminate information wherever I’ve been - Pittsburgh, Phoenix, here - just trying to help people. I’ve been the first Black bartender to work at a bunch of local places.”

The program is a dynamic one that involves much more than knowing how to mix a sazerac. “We hopefully will have two intakes a year, and the course is twelve weeks per intake. As well as bar skills, we focus on things like mental health, and how people can advocate for themselves.”

“We have this thing called the ‘externship’, where we place people. We have a guy we just placed for six weeks over at Cure, and if it leads to a job that’s great, and if not it’s valuable experience. Another person worked at Jewel of the South with Chris Hannah and now they have a job there. We have a good hit rate, graduates are managing, running wine programmes, the whole thing. Some people also use their new skills to expand their own businesses.”

It’s an inspiring project, and it seems fitting to hear about it in such an inspirational place. If Studio Be reflects what it is to be Black in America, Turning Tables improves people's chances of becoming what they dream of being.

To find out more about Turning Tables NOLA, go to www.turningtablesnola.org

Studio Be is at 2941 Royal Street, and is open Wednesday through Sunday from 2pm-8pm.

More information here: studiobenola.com